When I first began meditating within the Osho community at a young age, I was struck by the recurring emphasis on the idea that we are not our minds, a concept woven into all my Master’s teachings. This notion often confronts us as we embark on our yoga or meditation practices, typically pursued in the Western pursuit of “feeling better” and alleviating psychological or physical suffering. Yet, littlen do we realize that this journey extends far beyond mere well-being, delving into our very conception of existence, particularly our understanding of who and what we are.

The realization that we are not our minds dawns upon us gradually over the years, through dedicated practice and immersion in teachings vastly different from those of our upbringing, namely the philosophies originating from the East. Frequently, we assimilate certain concepts without truly grasping their history and profound implications, adjusting them within our existing framework of beliefs and synthesizing a highly individualistic, syncretic philosophy.

It’s true that even in the Western context, albeit expressed with different terms and references, we have come to understand that we are not solely defined by the aspects with which we immediately identify: nationality, biological sex, preferences, and aversions shaped by our personal biographies. Sigmund Freud shed light on some of these internal forces, which are both intrinsic to us and yet beyond our control. He coined a term for them within a well-defined structure of being: the unconscious—an unsettling, dark realm that gives rise to actions, emotions, dreams, ideas, and slips of the tongue, all in contrast to the ego we believe encapsulates us. The unconscious is deeply ingrained within us and yet simultaneously eludes our grasp, often dominating us against our will.

Clinical psychology once again comes to our aid through the words of Massimo Recalcati, who explains how the first great stranger is actually our own heart:

“The heart that each of us carries at the center of our chest, upon which our life depends, beats without our reason or will being able to command its rhythm. It is an elementary paradox inscribed at the core of life: the heart that sustains life is our own, yet it is simultaneously a pump that operates regardless of any control. The life of the heart transcends our own life while being at the center of it.”

What we are exists at a level beyond our control is a common experience even for women during pregnancy: the child happens within me, I am doing it and at the same time I am not doing it at all. The mystery of life unfolds in all its grandeur, revealing our limited zones of action and decision. We can accompany existence, be present as it unfolds, but it resembles much more surfing on a great wave than deliberately directing ourselves from point A to point B. Every action is part of an interdependent zone so vast that it is impossible to establish all its variables without entering into a nesting doll that inevitably ends up pointing to the infinitely small.

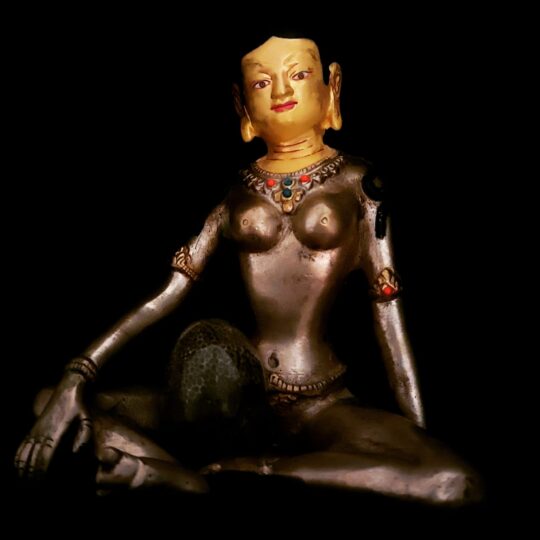

In addition to pregnancy, sex is another major avenue available to all where we encounter autonomy in the excess of life. It is indeed the experience of opening ourselves to the great Other in all its forms that inevitably turns the key to the presence of energies that inhabit us and yet transcend us.

Recalcati further states:

“Isn’t the life of the heart, as Freud would say, an experience where the most intimate familiarity and the most radical estrangement intersect? Isn’t the autonomous power of life, its excess, always partly foreign to itself?”

When we undergo energetic experiences such as Reconnective Healing, Bioenergetics, or Kundalini energy awakening, we consciously experience that excess, that being which we are and yet transcends us, that existence which is not merely a fantasy because it is typically beyond our field of consciousness. Indeed, to continue our quote:

“It is something that usually goes unnoticed. The condition for life to be ‘naturally’ alive is, fundamentally, to always partially forget oneself.”

Whether we perceive it as deeply buried personal emotions within our bodies, which, through deep breathing, seize control over our behavioral faculties during a Bioenergetics session, or as impersonal cosmic energies activating our muscles as in Reconnective Healing, or even as the primal Kundalini serpent rising from base to crown, shaking us to our core until we open ourselves to the divine, in those moments, something takes hold of us. Is this “something” me or not me? Are these forces separate from myself? Who, then, am I?

In this contemplation, we set aside dissociative experiences often invoked to explain what science cannot or perhaps refuses to acknowledge, yet ultimately cleverly appropriates, unable to deny them any longer, perhaps renaming them as with mindfulness—a term that masks the practice of meditation—only to market it, perhaps with a pharmaceutical label attached. Dissociation encompasses all out-of-body experiences, while near-death experiences represent vestiges of neurological activity in a dying brain, a reductionism driven by fear that seeks to control even the uncontrollable through labels, rather than employing rigorous methods in the pursuit of understanding and expanding the horizons of knowledge. Consider the fate of the frequently cited Jung, relegated to the hands of charlatans after being barred from certain universities that adhere strictly to “evidence-based” approaches. Yet Jung, through the creation of the concept of the collective unconscious, also sought to name phenomena that resist all attempts to reduce being to mere biological byproducts.

Whether it’s deeply buried personal traumas, overwhelming feelings of inadequacy, or perceptions of external forces as foreign, superior, or supportive, we are continually immersed in this vast Otherness, perceived by our minds in shades of the chthonic or the celestial, emanating from within or without. Our brains strive to maintain an illusion of control, filling in gaps with deductions, as modern neuroscience clearly illustrates.

Yet, when we encounter these phenomena through specific practices we actively seek out, that’s when fear emerges. Merely discussing the notion that we extend beyond our rational minds, or debating within both Eastern and Western conceptual frameworks, remains relatively benign. However, it’s during direct experience—when bodily mechanisms slip from our control, unconscious contents surface, visions arise, and insights deepen—that mental boundaries and limited understanding collapse.

In these moments, consciousness expands, much like a weary gaze broadens upon leaving the confined horizons of a city for the vastness of the countryside, refreshing and opening up the mind, reducing the monotony of thought. However, the sudden intrusion of space into our mind or the manifestation of other energies moving through our bodies can be terrifying, unsettling our sense of control.

Admitting “I don’t know” becomes a profound challenge, revealing our reliance on familiar, albeit suffering-laden mental constructs. Yet, it’s this acknowledgment that potentially reshapes our understanding of reality—recognizing our philosophical, psychological, and religious frameworks as mere attempts to navigate a vast world that encompasses us both externally and internally.

In Osho’s ashram in Poona during the early 1990s, I distinctly recall the experience of fear of losing one’s sanity due to profound cognitive changes induced by meditation. This fear often accompanies individuals taking their initial steps into the realm of the non-mind, when identifications cling like points on an already tight-fitting garment. Returning to the finiteness and immanence of the body, or rather to the reassuring confines of ordinary presence, is always a significant key to allowing experiences of “non-self” to settle first and integrate later, experiences facilitated by certain practices.

Not to mention the terror at the collapse of belief systems, the sensation that collectively established shared reality is a chilling falsehood—another inevitable stage of the inner journey that often involves a collapse of the false, potentially leading to radical choices in our daily lives.

Another crucial point that inevitably emerges during diligent meditation and energetic techniques is the fear that anything beyond the purview of ordinary mind is demonic. Unfortunately, this is a deeply ingrained conditioning for those who have had intense religious upbringing, and they may perceive the forces releasing within their bodies as terrifying. Consider the unlocking of sexual sensations and increased physical sensitivity during Bioenergetics breathing exercises, or the appearance of external forces acting in a healing capacity on the body during a session of Reconnective Healing. This often brings forth countless unconscious religious representations followed by cinematic depictions of demonic possession, causing individuals to perceive themselves as dangerous sinners, to be terrified of the unknown within them, and consequently to avoid rather than seek understanding.

Conditioning deeply misleads us and further distances us from knowledge, representing a negative effect of organized religions that have perversely monopolized and corrupted transcendent forces for millennia. This has led the collective psyche to swing between superstition and terror, on one hand, and ferocious denial of anything unexplained by science, on the other—a denial born out of the need for balance after centuries of religious dominance.

Here, we are not discussing the distortions of reality stemming from deep psychological suffering, which fall within the domain of psychopathology and are extensively addressed by relevant authorities in appropriate settings. However, it’s worth emphasizing that pathologizing every form of extraordinary experience is an extremely violent attitude, not less harmful than demonizing or outright denying it.

Thus, when we encounter that famous “excess” beyond our everyday consciousness, numerous internal and external forces can trigger intense experiences of fear and resistance to the flow of consciousness.

In summary, the loss of bodily control, fear of repressed emotions, the emergence of painful memories, the sensation of invisible presences, or energies perceived as potentially malevolent, intervening in the body from the outside to heal, can obstruct the experience and the ability to remain present without succumbing to it. Observing it and, if necessary, deciding to interrupt it become challenging. This also opens a chapter that won’t be addressed here, as this isn’t the appropriate forum: the need to tailor meditation experiences and interventions of all kinds for individuals heavily traumatized, for whom certain techniques could do more harm than good.

From what I understand, however, for those embarking on the path of self-discovery without overly burdensome baggage, the only way to overcome the aforementioned obstacles is through relaxed and patient persistence, accompanied by an open yet scientific attitude, employing the most potent of mantras: “I don’t know.” Remaining present, embracing fear, always listening to it with respect as an evolutionary and indispensable mechanism, but also not identifying with its voices and questioning them when possible, is not only a highly advisable mental exercise but also a safe path to expand towards an increasingly broader vision of our reality. Additionally, engaging with those who have navigated similar challenges before us can certainly provide reassurance. There’s nothing quite as worthwhile as embarking on the journey of self-knowledge as multidimensional beings, as defined by Dr. Eric Pearl, trans-sensors, even if it means sacrificing a familiar reality for one that compels us to admit that we don’t know much about ourselves either.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.